Illumina's Search for a New Growth Algorithm

Diagnosing Illumina's multi-year growth slowdown, and thinking through what happens from here.

Five years ago, Illumina was an investor’s dream: a high-growth, high-margin monopoly in DNA sequencing - a “forever grower” market.

Fast forward to the present, and Illumina is routinely and openly compared to Intel - a once-dominant company that missed growth opportunities, lost product velocity, and ultimately, fell from leader to laggard. Illumina’s stock is down 71% from 2019 to now.

Once you’ve seen the Illumina/Intel analogy, it’s difficult to un-see, especially because both chip manufacturing and DNA sequencing have similar governing principles: consistent miniaturization, increased density, and lower cost per unit.

I do not believe the Intel analogy fits. That said, Illumina’s dependable formula for growth in the 2010s plainly does not work anymore. The critical question for the company’s future is whether it can develop a new growth algorithm for the 2020s and 2030s.

I’ll explore several different angles of Illumina’s current predicament: why it was so richly valued in the 2010s, why the growth algorithm stopped working, and what happens from here.

An N-of-1 Life Sciences Tools Company

Illumina has a compelling claim to be the most important healthcare company of the last 20 years1. Sequencing is pervasive across biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. In January 2020, the earliest COVID genome sequences came from Illumina instruments2. I’d guess that Illumina has been mentioned in the methods section of every edition of Nature and Cell issue in the last decade3.

As we’ve explored in previous posts, Illumina’s business model is beautiful: each instrument produces a 5-year stream of 80%+ gross margin consumables that are predictable, recurring, and purchased by customers with minimal new sales & marketing effort.

Throughout the 2010s, Illumina had a track record of growing revenue 20%+ and putting up industry-leading margins. In 2019, Illumina had grown sequencing consumables revenue at a 22% annual rate over the previous 5 years4, and generated 30% operating margins, despite meaningfully above-peer R&D and stock-based compensation spend.

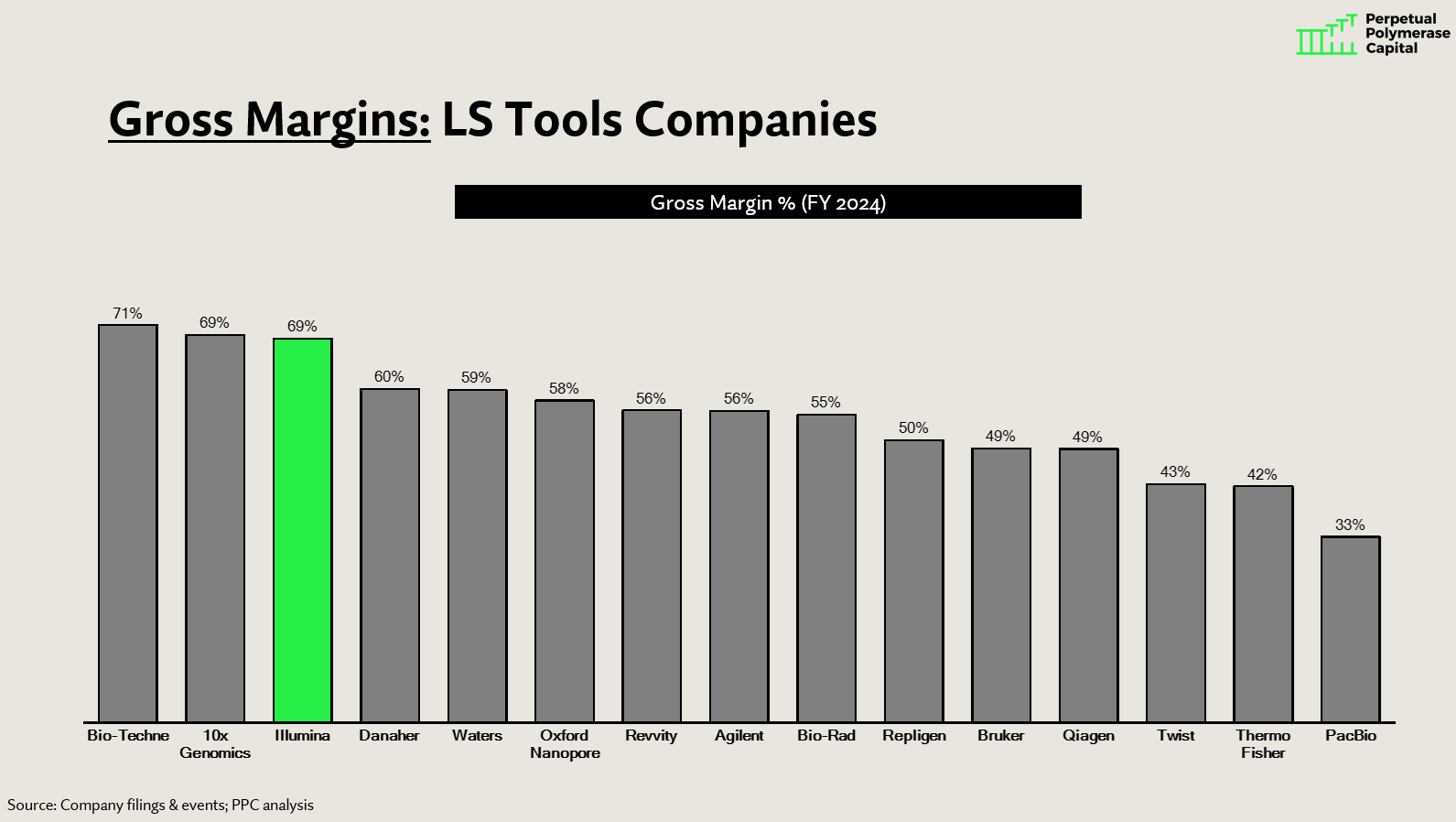

While much has changed since 2019, many parts of Illumina’s P&L are still exceptional. Illumina’s gross margin is in the upper echelon of life sciences tools companies.

Chart: Gross margin (2024), life sciences tools companies

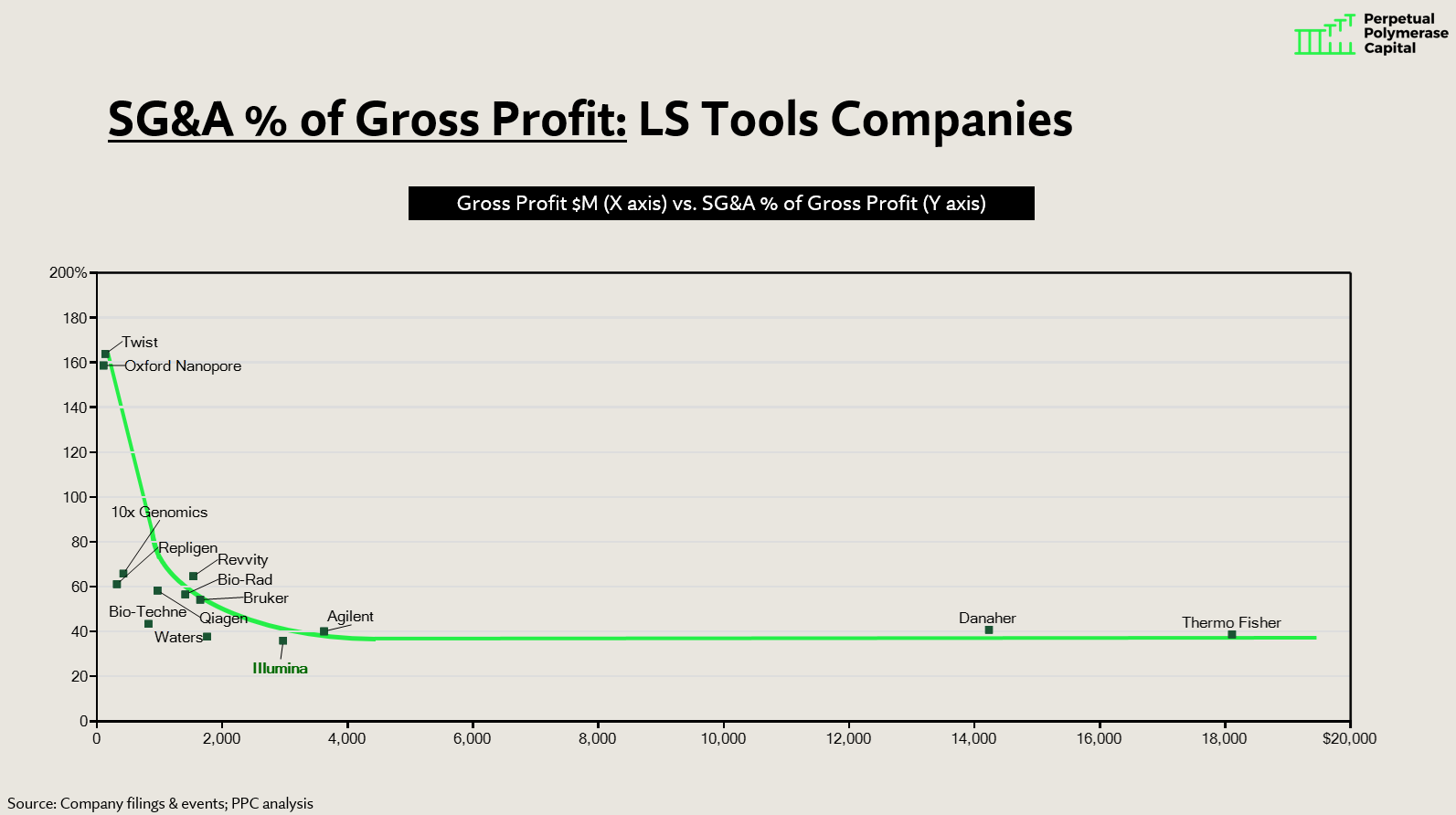

Additionally, Illumina has excellent sales efficiency, especially on high-end sequencers (NovaSeq X). As seen in the below chart, Illumina spends a lower share of its gross profit on selling, general & administrative expenses (SG&A) compared to other life sciences tools companies at similar scale.

Chart: Gross profit ($M) on the X-axis vs. SG&A % of gross profit on the Y axis. Companies that are “under” the curve are relatively more efficient for their scale (less SG&A spend per dollar of gross profit), companies that are “above” the curve are relatively inefficient.

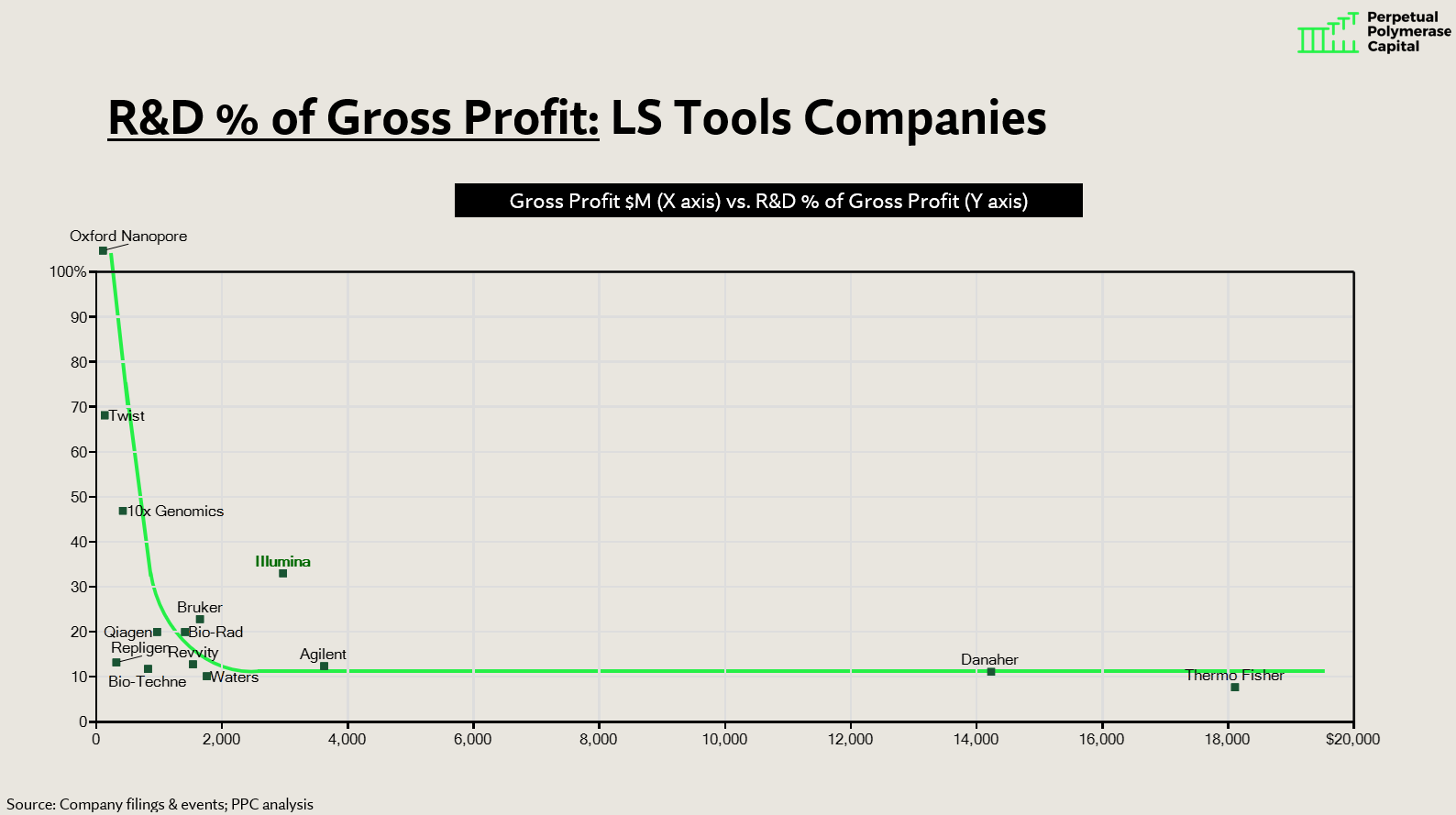

Illumina invests lavishly in research & development (R&D). Here, they are an outlier in the opposite direction - spending much more on R&D compared to peers.

Chart: Gross profit ($M) on the X-axis vs. R&D % of gross profit on the Y axis. Companies that are “under” the curve are relatively more efficient for their scale (less R&D spend per dollar of gross profit), companies that are “above” the curve are relatively inefficient.

Another way to look at Illumina’s outlier R&D is to compare the full cost structure across tools companies. In the chart below, companies with costs below 100% of revenue are profitable (total costs are less than revenue), while companies with costs over 100% of revenue are unprofitable. Compared to other profitable companies, R&D takes up a much larger share of Illumina’s costs.

Chart: Cost structure breakdown, LS tools companies (2024)

Historically, the market applauded - or at least tolerated - Illumina’s high R&D spend. Sequencing is an intellectually rich and fast-moving space, and Illumina had a track record of launching products that sustained their market leadership and revenue growth. Illumina’s flagship instrument (NovaSeq X) is effectively a giant microscope that sequences 7.5 trillion bases of DNA (75 human genomes) on a glass surface the size of a credit card in 48 hours with 99.9% accuracy. If anything warrants high R&D, it’s that.

With strong growth, strong margins, and dominant market position, Illumina commanded a rich valuation multiple. Between 2014 and 2019, Illumina traded at an average of 45x price to earnings (P/E) ratio, and never dropped below 30x P/E, indicating remarkable consistency of investor confidence.

From its 2019 zenith of 30% operating margins, Illumina’s P&L has fallen off precipitously. Every line item looks worse in 2024:

Gross margins have gone down from 71% to 69%

R&D share of revenue has gone up, from 18% to 23%

SG&A share of revenue has gone up, from 22% to 25%

Taken all together, operating margin has fallen from 30% to 21%

Moreover, sequencing consumables revenue growth decelerated rapidly: 7% annually in the 5 years ending 2024, compared to 22% annually in the 5 years ending 2019.

Often, when growth slows, investors look for margins to expand, or at least remain stable. But cases like this - rapidly slowing growth and rapidly declining margins - is a recipe for a protracted stock selloff.

So what happened?

The Growth Algorithm Breaks

There are many headwinds Illumina and other life sciences tools companies face right now: uncertainty in NIH funding (research customers account for nearly half of Illumina’s revenue), an unusually painful last several years in biopharma R&D (IRA and biotech VC slowdown), as well as geopolitical tensions in which Illumina is squarely in the crosshairs (the US BIOSECURE proposal sought to ban China’s major sequencing company, MGI, from the US, and China responded this year by banning sales of new Illumina sequencers in China.)

But my contention - and what I’ll focus on here - is that Illumina’s core problem has been in the making for longer. Specifically, the sequencing market slowed down meaningfully in the late 2010s/early 2020s, and this slowdown broke Illumina’s tried-and-true growth algorithm from the previous decade.

DNA sequencing has always been a highly elastic technology. Every time the cost of sequencing went down, demand went up even more, such that the overall market grew in revenue terms, because volume increases more than offset the price declines.

Indeed, between 2014 and 2019, Illumina’s sequencing consumables revenue roughly tripled, from $760M to $2.1B, a 22% annualized growth rate.

This occurred despite Illumina rapidly bringing down the cost of sequencing. Over this timeframe, I estimate the weighted average cost to sequence a gigabase (GB) of DNA on Illumina instruments went down from ~$45 to ~$15 per GB, a -20% annualized decline5.

Revenue growth of 22% in spite of 20% price declines implies that volume - the raw amount of gigabases of DNA sequenced on Illumina instruments - increased 8x between 2014-2019, a stunning 52% CAGR.

This, then, was Illumina’s growth algorithm in the 2010s: volumes grow 50%+, price comes down 20%, yielding 20% revenue growth6.

The first sign that something was amiss was 2019. At the beginning of the year, Illumina guided to 20%+ revenue growth for sequencing consumables. They ended up growing 14%, a curious miss versus expectations, especially since they hadn’t released a major new instrument with lower prices that year7.

Investors didn’t have much time to dwell on it, because coronavirus wreaked havoc on markets in 2020. Lockdowns caused Illumina’s consumables revenue to remain flat in 2020, but subsequently, consumables revenue shot back up in 2021, increasing 43%8. This was the fastest growth in nearly a decade. The 2019 blip was a distant memory - Illumina seemed as much a juggernaut as ever.

But the misses began to pile up. In 2022, Illumina guided to 15% sequencing consumable revenue growth, and ended up doing 1%. In 2023, Illumina guided to 8% growth, and ended up doing -4%9.

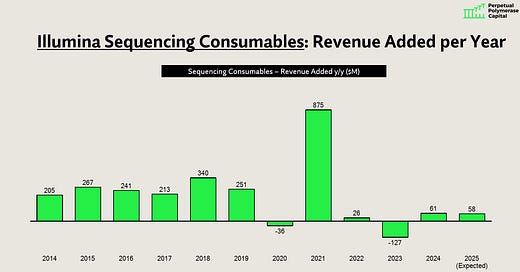

The trend was increasingly undeniable. As shown in the chart below, between 2019 (pre-COVID) and 2024, sequencing consumables revenue only grew at a 7% CAGR - a much slower rate than the 22% revenue CAGR between 2014 and 2019.

Chart: Illumina trailing sequencing consumables revenue CAGR by year (e.g., 2024 3-yr trailing revenue CAGR assesses annual growth between 2021-2024; 5-yr trailing revenue CAGR assesses annual growth between 2019-2024).

The core problem was that sequencing volume growth slowed meaningfully.

In 2024, Illumina’s management revealed that over the past 5 years, sequencing volume grew 25% per year. This is a far cry from the 52% annual volume growth for the previous 5 years.

But Illumina continued to bring prices down aggressively with the launch of new instruments (NovaSeq X) and new chemistries for existing instruments (X-LEAP chemistry for NextSeq). Herein lies the problem: if volume grows 25% per year but pricing declines 20% per year, this yields 0% revenue growth.

Illumina’s historical growth algorithm - 50%+ annual volume growth and 20% annual price declines yielding strong revenue growth - broke sometime in 2019 or the early 2020s. The below chart tells the story visually. Before 2019, Illumina reliably added $200-300M sequencing consumables revenue each year (e.g., if they did $1.5B in one year, they’d do $1.75B the next). After 2019, everything changed.

Chart: Illumina sequencing consumable revenue added per year, 2014 thru 2025.

Understanding the Slowdown

Why did Illumina’s volume growth slow? Is this a simple case of market maturation? Did Illumina miss the growth areas? Did competitors take share?

We will assess all three, but I believe the first answer is closest to the truth - the market simply matured.

More specifically, the research market matured, and the clinical market, while higher growth, hasn’t been able to drive overall company growth.

Here’s the evidence. In 2019, clinical sequencing consumables grew 20% year-over-year, while research grew 10%. At that point, clinical represented 40% of total consumables, and research 60%.

By 2023, clinical customers represented 50% of all consumables. This means that between 2019-2023, clinical sequencing consumables grew 14% annually (a strong if unspectacular growth rate), but more importantly, research consumables only grew 3% annually.

This fits with data on NIH funding trends. Both NIH projects mentioning “sequencing” and funding for said projects grew double digits throughout the 2010s, but decelerated to low-to-mid single digit growth in the 2020s10.

Chart: NIH projects and total funding mentioning “sequencing”, by year.

MRD to the Rescue?

Has Illumina missed critical growth areas? I don’t believe so.11

If we had to choose the most important growth area in sequencing right now, what would it be? The easy answer is minimal residual disease (MRD) testing for cancer, a hypergrowth diagnostics category that has rocketed Natera’s valuation from 18x lower than Illumina’s five years ago to 60% larger now.

Illumina definitely hasn’t missed this wave. On the contrary, every “Signatera” MRD test done by Natera (90%+ market share) and most MRD up-and-comers is performed on an Illumina sequencer.

The problem is that current MRD tests don’t provide much incremental revenue to Illumina. Each Signatera test uses about $100-150 of Illumina sequencing consumables12. Natera performed 500,000 Signatera tests in 2024. This implies $50-75M revenue to Illumina. That’s only 2-3% of Illumina’s $2.9B annual sequencing consumables revenue. Even if we assume that the MRD market quadruples over the next several years, to 2M annual tests, that’s only $200-300M MRD revenue for Illumina, 7-10% of Illumina’s annual sequencing consumable revenue.

To be clear, MRD is an important growth area, and one Illumina will be very happy to participate in, especially since it’s “easy” growth: the more tests Natera runs, the more revenue Illumina gets.

Is there a bull case for MRD? Illumina management argues that as MRD testing advances, each test will use more sequencing, perhaps $1,000 per test. For example, instead an upfront whole exome to catalog a patient’s cancer mutations, you could do an upfront whole genome, which entails 20x more sequencing. Also, for each follow-up MRD test, you could look for thousands of variants, rather than the 16 variants that Signatera uses. This would also use more sequencing.

Such “ultrasensitive” MRD tests from companies like Personalis have shown excellent preliminary results, especially in cancers like lung, which shed less DNA into the bloodstream. Natera recently announced such a test as well, although caveated that they expect their existing Signatera test to represent the vast majority of volumes.

I am skeptical that MRD tests using $1,000 in sequencing consumables will take the market by storm. Diagnostics companies really need 60% gross margins to make their own economics works. Even then, as we’ve seen with Exact Sciences (70% gross margin), it’s really hard to turn a profit. If diagnostics companies are paying Illumina $1,000 in sequencing consumables for each test, this means they’d need to get paid at least $2,500 per test to achieve a reasonable gross margin - and since Illumina isn’t the only cost, probably $3,000+. On average, payers reimburse ~$1,100 for Signatera right now13. Since Signatera is already an excellent, highly sensitive test, with broad reimbursement, I expect it to be challenging for ultrasensitive players to gain premium reimbursement from payers, and outcompete Natera commercially.

Are there other white hot market segments? Single-cell transcriptomics? I’m optimistic about single cell, but it has remained squarely an academic technique, and like sequencing, that market also hasn’t grown in 3 years. Spatial transcriptomics? Perhaps, but similar to single-cell, spatial is predominantly academic. Future applications in biopharma and clinical medicine are tantalizing, but still feel far away. Proteomics? Exciting, but nascent.

All taken together, I don’t see Illumina having missed major growth waves. That said, major market shifts are hard to see in advance, especially by investors. In 2025, it’s easy that say retrospectively that Intel missed the iPhone. I doubt anyone was offering that analysis in 2008. Perhaps there is a white hot area that Illumina is missing that I can’t see14.

Competition - Rational or Not?

The other major part of the story over the last 5 years has been increasing competition, especially from US-based upstarts like Element Biosciences (competing in mid-throughput instruments) and Ultima Genomics (competing in high-throughput instruments)15, both of whom offer lower consumable prices than Illumina.

Competition isn’t the direct cause of Illumina’s growth slowdown. Using public statements on competitor install bases, I estimate that together, Element and Ultima did $50M consumables revenue in 2024, compared to Illumina at $2.9B. If all the Element and Ultima revenue went to Illumina instead, at 2x the price (since Illumina consumables are more expensive than the competition), this would have added $100M to Illumina’s consumables revenue. With this addition, 2019-2024 sequencing consumable revenue CAGR only increases from 7% to 8% - still a far cry from the 22% of 2014-2019. Even if we add a further $200M, assuming that competition caused Illumina to discount more than they otherwise would - we only reach a 9% CAGR.

The critical go-forward question is whether competition is rational - and therefore enduring - or irrational.

I would consider competition rational if Element and Ultima themselves have strong gross margins and healthy unit economics. I would consider competition irrational if they are offering low prices via low gross margins and significant cash burn, funded by venture capital cash on their balance sheet.

Both Element and Ultima have deeply talented teams, have built excellent instruments, and have arguably demonstrated much more product velocity than Illumina over the last 5 years, despite a fraction of the R&D spend. But if we trace their private funding history ($500M+ for each), much of it came in the venture capital ZIRP extravaganza of 2019-2022. While that era is over, its impact may reverberate in markets for far longer, because the companies still have significant cash on their balance sheet. Eventually, unless these companies generate positive cash flows, they’ll need to raise more capital. If they’re still burning cash, equity financing will be increasingly hard to come by16, and new investors will demand more debt-like provisions, and require the companies to inflect towards profitability. This, in turn, may require them to raise prices in order to improve gross margins and cash flow17. But if that happens, they lose the very thing that made them attractive against Illumina in the first place.

In order to believe that competitors are here to stay, I need more evidence that they can take share with sound economics. Keep in mind, long-reads companies like PacBio and ONT have been around for more than a decade, and are still unprofitable - Illumina’s “force choke” on their gross margins and sales efficiency makes life as a competitor extremely hard.

As of a few weeks ago, there’s a new disturbance in the force. Roche, the pharma and diagnostics giant, plans to enter the market in 2026. Roche’s “sequencing by expansion” (SBX) chemistry looks to have good accuracy, sequences DNA very fast (can sequence a human genome in a few hours, compared to 48 hour runtime for Illumina), and, perhaps most critically, according to people who are much more well-versed in the COGS of sequencing consumables than I am18 - probably has a cheaper underlying cost structure. If this is indeed the case, it certainly seems like rational competition.

We’ll learn a lot more over the coming year as Roche enters the market. I believe it’s a real threat. But, crowning Roche an Illumina-killer - or even a major share taker - in a market that has been so hard to crack for so many companies over the last two decades, and is already seeing moderating growth - feels premature, and more a reflection of the market’s pessimism about Illumina.

Is Sequencing a Commodity?

One argument you hear from Illumina bears is that sequencing is becoming a commodity. According to this theory, it matters less and less what kind of instrument actually does the sequencing - it’s just a bunch of DNA letters. And the products used before sequencing (library prep) and after sequencing (informatics) are becoming more modular. Following this logic, it will be increasingly easy for competitors to take market share from Illumina.

I see cracks in this argument.

First, it’s worth keeping in mind that despite Element and Ultima pricing significantly lower than Illumina, they haven’t yet gained correspondingly significant market share, even narrowly looking at new instrument placements. In 2024, Illumina placed about 270 NovaSeq X instruments. Ultima placed perhaps 25 UG-100s. This is more than a ten-fold delta in placements, despite the 50% consumable cost differential.

And many of the more “commercial” customers within Illumina’s install base - diagnostics companies like Natera, Guardant, Exact, and Adaptive - recently decided to switch from old Illumina sequencers to the NovaSeq X, not the Ultima UG-100.

There’s a lot that goes into switching an instrument. Lab workflows need to be changed. New library prep kits need to be procured. Informatics pipelines need to be re-built. Instrument reliability needs to be clearly established. Nuances of that particular sequencing chemistry (e.g., if it is more or less accurate in certain regions of the genome, better or worse with homopolymers) need to be analyzed, understood, and controlled for.

If you talk to many lab directors about switching a production grade sequencer, you can see the color immediately drain from their face. This is a major undertaking, to be done rarely, with a lot of preparation, and only if there are large benefits on the other side. Some customers (especially academic cores) may buy new instruments to play with, run new workflows on, and/or scare Illumina into giving them bigger discounts. But shifting existing workflows and large volumes takes a lot of work.

Even switching from one Illumina sequencer to another is a challenge. Adaptive Biotechnologies (MRD testing for blood cancers) has been talking about switching from NextSeq to the NovaSeq X for the last year and a half19, and plans to finally make the cutover in late 2025 - a two year process.

All of this casts serious doubt on the commoditization theory.

The best counter-argument is that I’m too focused on the value and not the derivative. Sequencing is obviously not a commodity, but it is becoming more of a commodity on the margin. The derivative points towards commoditization, and the derivative is what matters over the long term. I will grant this but probably still disagree with the argument.

Conclusion: The Search for Growth

The last half-decade has been brutal for Illumina. Even if it is not as obviously in decline as Intel, the market no longer supports its tried-and-true growth algorithm.

How can Illumina grow going forward? Simplistically, there are three possibilities:

Re-accelerate volume growth

Slow or stop the price declines

Grow the non-sequencing business: single cell, spatial, etc.

On #1, I find a major volume acceleration unlikely, and more importantly, outside of Illumina’s immediate control. Markets don’t magically re-accelerate absent extreme changes, especially markets as big as sequencing is now. As we’ve seen, the opposite usually happens: market growth rates naturally decline over time. Illumina has seen some re-acceleration with the launch of the NovaSeq X (2024 volume growth was +37%), but it was only catalyzed by the lower pricing (-25%). Together, 37% volume growth and 25% price headwinds yields only 3% revenue growth.

On #3, Illumina is investing heavily in single cell, spatial, and to a lesser extent, proteomics. I expect these be contributors to Illumina’s go-forward growth algorithm. But, combined, single cell and spatial are currently 1/5 the size of the sequencing market, and more importantly, they’re not exactly hypergrowth markets either. The market leader in both of these areas, 10X Genomics, is also struggling to grow. That said, I do believe that growth rates for both will rebound when macro conditions improve.

Illumina has fewer endowed advantages in these markets compared to sequencing. They’ll have to compete against 10X, a company that is several years ahead, has an Illumina-scale install base in single cell, and whose product velocity and innovation track record has been much stronger than Illumina’s over the last several years20.

To be clear, Illumina absolutely should invest in new greenfield opportunities like these. Great CEOs - and great companies - have a knack for investing big in things that are going to be important in 5 years, before it’s apparent to outsiders.

But for now, #2 - slowing the price declines - seems to be the clearest way for Illumina to return to sustainable growth. And if Illumina just does nothing, #2 will happen naturally. As customers complete the transition from the the NovaSeq 6000 to the NovaSeq X, pricing declines will moderate, unless Illumina actively introduces new instruments or flow cells to cut prices further.

What kind of volume and price combinations will support dependable, high-single digit revenue growth for Illumina? Assuming volume grows at 20% annually over the next 5 years and pricing headwinds moderate to 10% per year, this supports 8% revenue growth.

Chart: Illumina sequencing consumable revenue growth in various volume/price scenarios. Scenarios with >8% annual growth are highlighted green.

This strikes me as doable. The big question, however, is whether the game on the field will allow Illumina to do this. Will Roche come in and price disruptively, forcing Illumina to respond? Will Element and Ultima evade the force choke and continue to take share?

My expectation is that market-wide price pressure will moderate rather than continue to decline at historical rates. The up-and-comers - Ultima, Element, Roche - don’t want to gain share in a maturing sequencing market only to be stuck in a race to the bottom themselves. Illumina only generates $1B free cash flow per year. Roche does $17B. Is Roche, a Swiss pharma giant, going to be hyper-aggressive on pricing in an attempt to grab a couple hundred million of cash flow per year in the sequencing market? Perhaps, but if I were Illumina, I might be more comfortable with Roche as a competitor than a crazed startup with $1B funding from Softbank.

For the last 20 years, the driver of value in sequencing has been who can deliver more sequencing volume at a lower cost. The sheer pace of volume growth allowed this to be a winning growth algorithm. In the future, with more modest volume growth, the driver of value may change. Perhaps it becomes who can justify a given cost with additional features (e.g., ultra-fast results, ultra-high accuracy, longer reads21). Perhaps it becomes something entirely different.

For Illumina, this is perhaps both reassuring and intimidating. Reassuring, in that they remain the center of gravity in sequencing. While the market has matured, it’s hard to see an area where Illumina is losing. Intimidating, in that growth in the future will require a very different algorithm to that which worked so extraordinarily well in the past.

This would be a fun debate. Eli Lilly, with tirzepatide? Moderna/Pfizer/BioNTech, with the COVID vax? Merck, with Keytruda and the immunotherapy revolution? More depressingly, United Healthcare?

Given that the COVID genome was first sequenced in China, I assumed it might have been on an MGI. sequencer. But according to the internet, Zhang Yongzhen used an Illumina instrument.

I’m a deep believer in the importance of highly charismatic names, and Illumina has one of the all-time great company names. Illumina. So cool.

I mostly focus on sequencing consumable revenue growth here. Consumables are the best proxy for underlying demand, and are the majority (~70%) of Illumina’s revenue. Instruments can be lumpy based on when new instruments are launched, and is more impacted by macroeconomic factors (e.g., recessions.)

This is a blended number across instruments - high-throughput, mid-throughput, and low-throughput. It’s an estimate (cross-referenced by Illumina’s own disclosures on cost per GB across platforms, and NIH data on sequencing costs).

An easy napkin math exercise for this: assume 1 volume and $1 price. Thus, $1 revenue. Volume goes up 50%, to 1.5. Price goes down 20%, to $0.80. 1.5 * $0.8 = $1.20 revenue, a 20% increase.

The 1-2 years right after a new sequencer launch tends to be when the most aggressive price declines happen, since the highest volume customers (e.g., Broad Institute, Wellcome Trust) are the first to move to the new machines in order to take advantage of the better pricing.

In retrospect, 2021 was a year of enormous pull-forward and one-time COVID demand in life sciences tools. Incredibly, the median LS tools company in my coverage universe grew 21% in 2021, compared to only 5% in 2019.

Perhaps the best sign that management was on the hunt for growth was the catastrophic acquisition $8B GRAIL acquisition in 2021. GRAIL, a nascent cancer diagnostics company focused on early cancer detection (using Illumina sequencers), blew a gigantic hole in Illumina’s balance sheet (Illumina paid $3.5B upfront cash, $4.5B of share dilution, and funded GRAIL’s $500M+ annual cash burn for several years) as well as an order of magnitude more brain damage (overzealous EU regulators tried to block the acquisition, and Illumina closed the acquisition despite this, leading to 3 years of legal hell before finally spinning off GRAIL at 1/20th it’s acquisition value in mid-2024). The great “what-if” in LS tools is if Illumina had only decided to acquire Natera in 2021 rather than GRAIL. Natera was trading at $5B market cap at time of GRAIL acquisition, so assuming a 30-40% premium, they could have purchased it for a similar price.

This is a very lossy analysis - NIH is only a fraction of Illumina’s research consumables; sequencing might be taking dollar share within certain projects; maybe some grant applications that use sequencing don’t use the word. Etc, etc. But I find it to be directionally helpful.

Intel missed big growth opportunities. Famously, Intel passed up the chance at chip manufacturing for the iPhone, and was late to adopt new process technologies like extreme ultraviolet lithography.

The “upfront” one-time whole exome sequencing uses ~$200 worth of Illumina consumables, while the recurrence monitoring tests cost ~$20 worth of Illumina sequencing, since it’s a PCR-based assay that only amplifies 16 targets. In 2024, Signatera volumes were roughly 50/50 between upfront and recurrence tests, thus, ~$120 of Illumina consumables per Signatera test on a blended basis.

More precisely, payers often pay $2,000+ for Signatera, but then also don’t pay Natera at all ($0) 40% of the time.

If anyone has perspectives here, let me know.

MGI, aka Complete Genomics, is also a competitor, but this is a Chinese company and, given the privacy and security implications of DNA sequencing, has vanishingly low penetration into the US market. I expect MGI to win the Chinese market (especially since the Chinese government has increased its aggression towards Illumina in China, banning them from selling new sequencers.) MGI will also be competitive in emerging geographies, e.g., LATAM and Africa, and to a lesser extent, Europe.

Most funding rounds from VCs have a 1x “liquidation preference”- meaning that in an acquisition scenario, VCs get paid back their initial capital before employees or management teams make money. If a company raises $500Mfrom VCs, and then gets acquired for $600M, the VCs would take the first $500M, and then employees and management would split the leftover $100M. The issue with liq prefs is that as companies continue to raise capital, it becomes less likely that VCs get their money back even in an acquisition. For example, Ultima has raised $600M to-date. This means that for investors to get their money back, Ultima needs to sell for at least $600M. But with excellent, market-leading, cash-flow positive life sciences tools companies like 10X Genomics only trading at $1B on the public markets, despite being 10x the revenue scale of Ultima, how confident can you be that Ultima would fetch a price higher than $600M? In subsequent funding rounds, you’ll oftentimes see new investors try to make their money “senior” to the earlier rounds - meaning that in an acquisition, they get paid back first, before the early investors, who are themselves before management and employees. This can all get messy and acrimonious, and moreover, demotivating for employees and management. If you work at a company that’s not worth the liquidation preference, you’re working to get VCs paid back on their investment.

Cutting sales & marketing is usually self-defeating and causes revenue to decline. Cutting R&D can work, but it also harms long-term growth. Cutting G&A can also provide modest benefits, but small private companies usually don’t overstaff wildly on G&A, so it can be hard to find places to cut meaningfully.

Keith Robison at Omics!Omics!, Nava Whiteford at ASeq, and Albert Vilella at Rhymes with Haystack.

AS a reminder of just how powerful the NovaX is, Adaptive is swapping out a fleet of 32 NextSeqs for 2 X’s (and 2 only for redundancy purposes - they could have done 1)

The stock chart will not tell you that, but I will.

I’d be very interested if Illumina could do ultra-rapid sequencing like Roche or ultra-high accuracy like Ultima’s ppmSeq (Q50-Q60.) My understanding is that ultra-fast mode like Roche is difficult to do given Illumina’s SBS chemistry. But I’d be interested to see what they could do if they really pushed SBS to its absolute max. And they also do spend some portion of the annual R&D budget on nanopore sequencing, although this has been kept deeply under wraps.

Your force choke theory can only apply to products with similar features to ILMN. Differentiated products are bought for different underlying reasons than cost per base, although it’s a factor. No, not all sequencing is the same. The profile of bases, and the workflows they can fit into also breaks up the purchasers. Large expensive boxes can only be bought by a relatively small number of labs, on grant funding mostly. That segment can certainly mature.

Thanks for putting all of this together. I learned so much from your analysis!

One thought on the clinical market and growth potential. Aside from MRD, you mentioned a price point around $2500/test to achieve a reasonable gross margin. 3K seems to be the magic number for whole genome reimbursement rates, meaning growth in the WGS test market could be good for both clinical labs AND Illumina. I would argue also good for certain patients.